Growth-stage companies regularly face a difficult situation: strong fundamentals, demonstrated traction, and a clear path forward, yet traditional capital markets may not be cooperating. Valuations fall short. Institutional investors remain cautious. The timing for a dilutive round is wrong.

In these moments, advisors and capital partners play an important role in recommending alternative options when traditional equity paths are blocked or suboptimal. Venture debt is an underutilized tool in the growth-stage capital stack and understanding when and where it fits can help you deliver better outcomes for clients who need capital but shouldn't (or can't) raise equity right now.

This guide provides a framework for evaluating venture debt: how it works, when it fits, and how to position it as a potential strategic option rather than a last resort.

Venture debt is minimally dilutive term financing designed for growth companies. Unlike bank loans, it doesn't require hard assets or profitability. Unlike equity, it doesn't require giving up 20-25% of the company, or the additional constraints that accompany most equity investments (e.g. board seat, liquidation preferences, etc.).

Most venture debt facilities share a common structure:

The most valuable conversations you can have with clients happen when they're facing a capital gap, but the equity path is blocked or suboptimal. The capital gap doesn't necessarily suggest anything negative. Maybe your client is overachieving, and you want more runway. Here's when to bring venture debt into the discussion:

Your client has grown since their last round, but current market conditions mean they'd have to raise at a flat or down valuation. Instead of diluting at the wrong price, venture debt can extend their runway, sometimes by years, giving them time to hit the metrics that justify a better valuation or for markets to recover.

Example: A SaaS company at $6M ARR, growing 40% YoY, raised their last round at a rich multiple. In today's market, new investors are offering a valuation far below what the founders and existing shareholders believe is fair. A $5M venture debt facility buys time to reach $10M ARR and re-engage investors from a position of strength.

Sometimes the issue isn't valuation: it's velocity. Equity rounds that once closed in 8 weeks are dragging to 6+ months. Your client can't afford to wait that long.

Venture debt can serve as a bridge while the equity process plays out or eliminate the need for that round entirely if the company can reach cash-flow positive with the additional runway.

Your client is 6-12 months from profitability or a significant milestone but needs capital to get there. Raising equity at this stage means diluting right before the next major valuation hurdle.

A small venture debt facility can provide the final push to break-even or to a milestone that dramatically changes their negotiating position.

Some founders are philosophically opposed to heavy dilution.

For these teams, venture debt offers growth capital without governance changes, board seats, or forced liquidity timelines.

Smart CFOs don't think in "debt or equity." They think in blended cost of capital.

Even when equity is available, the all-in cost of debt can still be dramatically cheaper than equity, particularly in a growth company.

Example: A company needs $15M.

Same growth plan, more ownership preserved for founders, key employees, and existing investors.

Not every company is a fit. Here's what lenders typically look for:

Companies that are pre-revenue, burning cash with no path to sustainability, or treating debt as a last resort typically aren't good candidates.

Transparency builds trust. Here's what the numbers typically look like:

Warrants give the lender the right (but not obligation) to buy a small amount of equity in the future, usually at the current or last round's price.

Typical patterns:

Clients should expect:

When you're advising, encourage clients to compare total cost (interest + fees + expected warrant dilution) with the dilution from an equivalent equity raise.

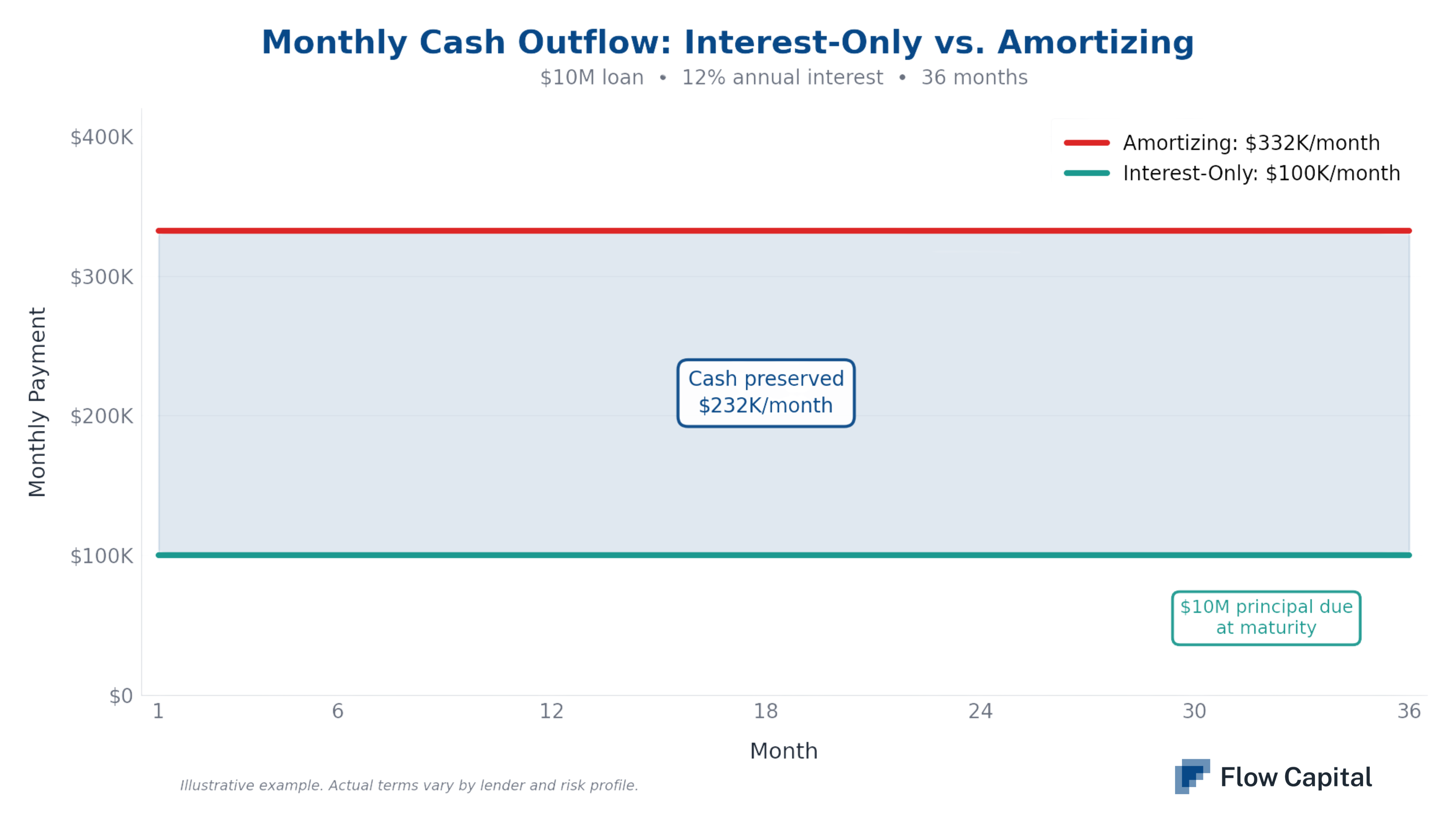

Most lenders provide some interest-only period (IO), although occasionally a lender will provide a loan that is interest-only for the full term. The IO period can make a huge difference in the size of the total loan, as well as the cash that leaves the business rather than staying to fund growth.

For example, here are cash outlays for a $10M, 12% interest, 3-year loan:

Lenders might provide a 6-, 12-, or 18-month IO period, and they might only amortize 50% or 75% with a lump sum payment at maturity for the remaining principal, but any way you slice it, amortization can be a huge drag on cash flow. When advising clients, tell them to look very carefully at the amortization terms and the capacity of the business to support such payments. Often, if you can find a lender willing to provide IO for the full term, the improved margin of safety in cash flow may be worth accepting a slightly higher headline interest rate.

When a client asks, "Should we consider venture debt?" walk them through these six questions:

Good answers:

Red-flag answers:

Debt wants a specific, high-confidence plan, not generic "runway extension."

Ask them to complete this sentence in English: "We'll repay or refinance this debt when ______ happens."

The blank should be something credible and measurable: a follow-on equity round at a reasonable multiple, reaching break-even, refinancing at a lower cost, or a strategic exit.

If they have institutional investors:

Lenders will ask these questions. Having investor buy-in up front makes the process smoother and the company more attractive.

The best time to raise debt is usually when you don't desperately need it:

Raising with days of runway left leads to worse terms, or no deal at all.

Flow Capital provides venture debt financing to growth-stage companies across the US, Canada, and UK. If you have a client exploring their capital options, we'd welcome the conversation.